On 13 December, in an enthusiastic press release, the European Commission welcomed the political agreement reached on the same day between the European Parliament and the European Council on the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), whose principle is to tax the carbon content of imports. According to the Commission, this mechanism will be the Union’s reference tool for encouraging cleaner industrial production in third countries: “a European solution to a global problem!”

A reading of the European Council’s press release of the same day is much more discreet: this agreement is of a “provisional and conditional” nature, “the CBAM can only be formally adopted once the elements relevant to the CBAM have been resolved in other related dossiers” and that, in the first instance, it will be limited “to reporting obligations only”…

Thus, the establishment of this mechanism is closely linked to many of the initiatives and proposals made by the Commission when it presented its Green Deal on 14 July 2021. Therefore, a new (provisional) agreement between the Parliament and the Council was reached 5 days later, after 30 hours of negotiations. So, before detailing the CBAM mechanism, let’s look at the context in which this draft Regulation is set.

CBAM and its context

Its main context is the upward revision of the European ambition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. This ambition is reflected in five highly interconnected texts[1], including a proposed revision of the ETS directive for the 2021-2030 phase (and the proposed CBAM regulation). These texts provide for:

- Raise the overall ambition of the ETS from a 55% reduction to 61%. (The agreement would be 62%).

- Extend the aviation ETS to the maritime sector.

- Create a new ETS for buildings and road transport. (This is to be in line with Germany… but with the introduction of some protection against excessive prices. According to the Council agreement, this price cannot exceed 45€/tCO2 or ~0,15€/l petrol or 8,33€/MWh, which is the level of impact of the French “carbon tax” which no longer says its name. German mechanism, French price!)

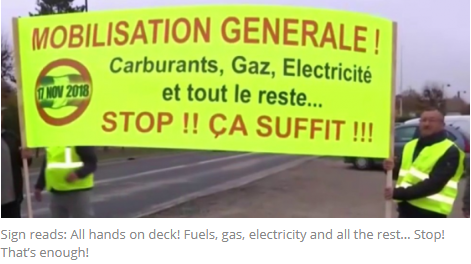

- Create the Social Climate Fund for the energy transition: the hoped-for antidote to the “yellow vests”, which could represent up to €86.7 billion.

- Strengthen the Innovation Fund (which could finance contracts for difference in the hydrogen sector, for example – the fund goes from 450 to 575 million allowances, ~€50bn).

- Revise the rules on free allocations, including a review of benchmarks and above all the phasing out of free allocations following the introduction of CBAM, with its total removal in 2035. This is the point that worries European manufacturers the most and this concern has been well conveyed by the Council. (Final consumers would also be entitled to be concerned).

- Maintain, as far as the Market Stability Reserve is concerned, the doubling of the thresholds and of the admission percentage until 2030 – i.e., admission rate: 24% threshold and minimum number of allowances to be placed in the reserve: 200 million allowances.

Furthermore, as the Council notes: “the financing of the administrative expenditure of the European Commission, which will assume many of the centralised administrative tasks related to the CBAM, will have to be decided in accordance with the annual EU budgetary procedure”.

The CBAM

The Commission’s proposal can be summarised as follows:

- The principle of the mechanism is to “create a historic tool to set a fair price on the carbon emitted during the production of carbon-intensive products entering the EU, and to encourage cleaner industrial production in third countries.”

- The scope of application are imports of the following sectors: cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity and hydrogen.

- The practical details are as follows:

- This mechanism will lead to the creation of new certificates that do not seem to be tradable. Their validity period is limited to one year and the surplus can be resold at the purchase price: CBAM Certificates. These certificates will be issued by Member States at the price set by the Commission (based on the prices of the latest auctions) and the proceeds will be “mostly” paid back to the Commission: “Although revenue generation is not an objective of the CBAM, it is expected to generate additional revenues, estimated for 2030 at more than €2.1 billion”. We should note that the issuance of these certificates will not be limited in their amount and its pricing fixing system is similar to that used by a consumer who could, ex post, buy electricity at the latest auctions prices.

- Each importer will have to calculate the intrinsic emissions of each product included in the applicable scope and surrender the corresponding number of certificates. This calculation will have to be done according to precise modalities and will be subject to verification.

To give this scheme a chance to be compliant with WTO (World Trade Organisation) rules, two provisions have been added:

- Article 31: “CBAM certificates to be surrendered […] shall be adjusted to correspond to the extent to which EU ETS allowances are allocated free of charge”.

This article does not make any reference to the inclusion of any CO2 compensation in the price of electricity for energy–intensive enterprises (cf. European Commission communication of 21 September 2020 on guidelines for certain State aid measures in the context of the greenhouse gas emission allowance trading scheme after 2021 (C [2020] 6400 final)).

- Article 9: “An approved registrant may request […] a reduction in the number of CBAM certificates to be surrendered in order to take account of the carbon price paid in the country of origin”.

Fortunately, any revenues potentially generated by the issuance of these certificates are not a CBAM objective; it seems sufficient that the exporting country taxes this export on the basis of the amount of emissions and the European CO2 price for the resulting revenues to remain in the country.

On the other hand, for the calculation of the intrinsic emissions of electricity, this regulation is more generous for non-EU countries than for EU countries: the cost of the ETS (via CBAM certificates) will only apply to the average emissions factor, whereas in Europe the price of electricity includes a carbon tax via the ETS in line with the marginal emissions factor. For example, for France, this emissions factor is estimated at 0.51t/MWh (Decree no. 2022-1591 of 20 December 2022, art. 1) whereas the average emissions factor is about 10 times lower.

Conclusion

On 18 April 2023, the European Parliament adopted the five texts concerned by the 18 December agreement. These texts were subsequently validated by the Council on Tuesday 24 April. The way now seems clear for the CBAM, which will require a certain number of implementing texts. Let us hope that this mechanism will be something other than a magic formula opening Europe’s doors to carbon-based or even delocalised products, but rather the protection of a strong and clean European industry!

Philippe Boulanger